Are Bishops Actually Better than Knights? A Data-Driven Analysis

A Centuries-Long Question

In chess, few debates have persisted as long as the relative value of bishops and knights. These two minor pieces, with completely different movement patterns, have been valued equally at three points for centuries. The knight moves in its distinctive L-shape, unchanged since the game of chaturanga in 6th century India. The bishop glides diagonally across the board, a power it gained when the medieval "elephant" piece evolved into its modern form. Despite these fundamental differences, both pieces have traditionally been considered equal in value.

To investigate this assumed equality, we analyzed over 700,000 chess games, including more than 500,000 from master-level players (2400+ rating) and 200,000 from amateur players across four rating bands. Our analysis focused exclusively on positions with exact material equality, examining how bishops and knights perform when all other factors are controlled. The findings challenge long-held assumptions about these pieces.

Historical Evolution: From War Elephants to Modern Pieces

The bishop and knight have ancient origins in the Indian game of chaturanga, where they represented different divisions of an army. The knight has always represented cavalry, maintaining its unique L-shaped movement for over 1,500 years—the only chess piece whose movement has never changed. The bishop's history is more complex: originally the war elephant, it could only jump exactly two squares diagonally. When chess reached Europe through Islamic conquests, the elephant gradually transformed into the bishop, gaining its modern unlimited diagonal scope.

This evolution created two pieces with contrasting characteristics. Knights can reach any square on the board regardless of color, but require multiple moves to cross it. Bishops move with unlimited range but are confined to squares of one color. This fundamental trade-off has contributed to the richness of chess theory and analysis that has been developed over the centuries, since the days of Lopez and Philidor.

Classical Principles: When Each Piece Excels

Classical chess theory provides clear guidelines about when each piece should be preferred. Knights excel in closed positions where pawn chains block long diagonals. They thrive when placed on central outposts, particularly on the fifth and sixth ranks where they cannot be attacked by enemy pawns. In endgames with all pawns on one side of the board, knights often outperform bishops because the bishop's long-range advantage becomes less relevant.

Bishops, conversely, dominate in open positions with clear diagonals. They excel in endgames with pawns on both sides of the board, where their ability to quickly switch between flanks becomes decisive. The concept of "good" and "bad" bishops, determined by whether a bishop's own pawns block its diagonals, adds another layer of complexity to piece evaluation.

One well-established principle is that knights and queens work particularly well together. While the queen already possesses diagonal movement like bishops, knights' complementary movement patterns allow them to coordinate with queens to create threats on both color complexes simultaneously. Similarly, bishops pair well with rooks, covering the diagonals that rooks cannot reach.

The Numbers Game: Historical Valuations

While the traditional point system assigns both pieces a value of three, numerous attempts have been made to refine these values. In 1999, International Master Larry Kaufman conducted extensive database analysis and concluded that unpaired bishops and knights are equal within 1/50 of a pawn, essentially a negligible difference. He valued both at approximately 3.25 pawns. World Correspondence Champion Hans Berliner's analysis suggested slightly different values: knights at 3.20 and bishops at 3.33.

More significantly, Kaufman's research revealed that when one side has the bishop pair and the other does not, the side with the pair should benefit from an advantage of approximately half a pawn. This finding has been incorporated into many modern chess engines and has influenced grandmaster play for decades.

Our Methodology

We analyzed games from two distinct populations. The master database contained over 500,000 games between players rated 2400 and above. The amateur database consisted of exactly 50,000 games from each of four rating brackets: 500, 1000, 1500, and 2000. These ratings are calibrated to Chess.com blitz ratings and were chosen to represent distinct skill levels while ensuring adequate sample sizes.

For each game, we examined positions at moves 15, 20, 25, and 30 to determine whether a bishop-knight imbalance existed. We included only positions with exact material equality (identical numbers of pawns, rooks, and queens for both sides). This strict criterion ensured that performance differences could be attributed to the minor pieces themselves rather than other material imbalances.

Statistical significance was determined using significance tests with p < 0.05 as the threshold. We converted winning percentages to centipawn equivalents using the standard FIDE formula to quantify advantages in familiar terms.

The Results: Challenging Conventional Wisdom

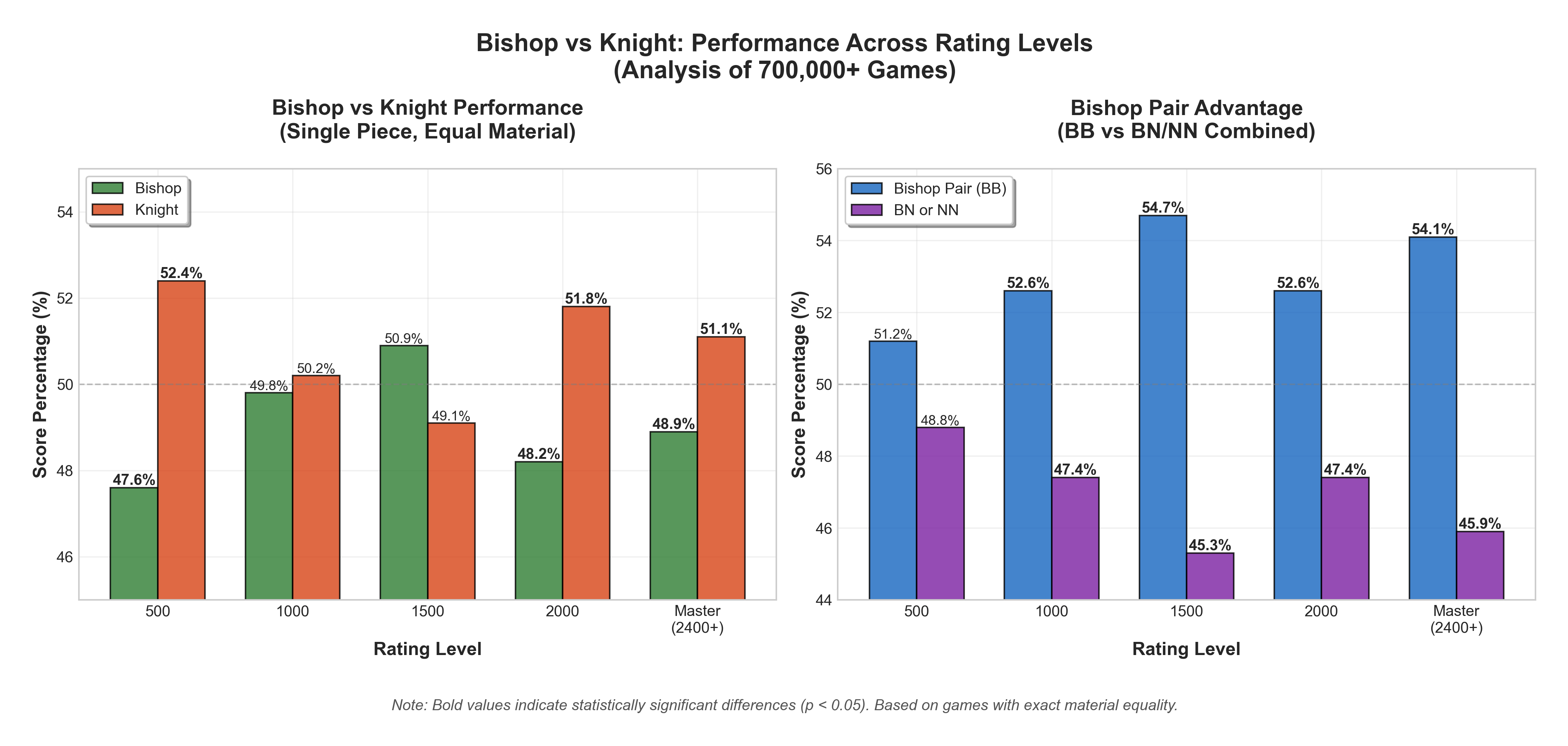

Bishop vs Knight performance across 700,000+ games. Left: Single piece matchups show knight advantage at most levels. Right: Bishop pairs consistently outperform mixed minor pieces and knight pairs.

Single Piece Performance (Bishop vs Knight)

| Rating | Bishop Score | Knight Score | Advantage (Centipawns) | Sample Size | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 47.6% | 52.4% | Knight +16 cp | 843 | p < 0.05 |

| 1000 | 49.8% | 50.2% | Knight +1 cp | 2,200 | Not significant |

| 1500 | 50.9% | 49.1% | Bishop +6 cp | 2,996 | Not significant |

| 2000 | 48.2% | 51.8% | Knight +12 cp | 3,431 | p < 0.01 |

| Master (2400+) | 48.9% | 51.1% | Knight +7 cp | 63,294 | p < 0.00001 |

The single-piece matchup data reveals an interesting outcome: knights slightly outperform bishops at most skill levels. This advantage is statistically significant at the 500, 2000, and master levels, ranging from 7 to 16 centipawns. Only at the 1500 level do bishops show any advantage, and this result is not statistically significant.

Understanding the Knight's Advantage

Several factors may explain why knights outperform bishops in practical play with equal material:

Tactical Complexity: Knights create unique tactical threats through forks and discovered attacks. Their non-linear movement makes these threats harder to visualize and calculate, particularly under time pressure. This complexity affects both players but disproportionately benefits the side with the knight.

Color Flexibility: Knights can attack and defend squares of both colors, while bishops are permanently restricted to one color complex. In practical play, this flexibility often outweighs the bishop's superior range.

Rating-Specific Patterns: At lower ratings (500), players frequently overlook knight forks and tactical shots. At higher ratings (2000+), players better understand how to restrict bishops and create favorable positions for knights. The 1500 level appears to be a sweet spot where players have developed sufficient tactical awareness to avoid simple knight tricks but haven't yet mastered the positional nuances that favor knights at higher levels.

Bishop Pair Performance (BB vs BN/NN)

| Rating | Bishop Pair Score | Opponent Score | Advantage (Centipawns) | Sample Size | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 51.2% | 48.8% | BP +8 cp | 960 | Not significant |

| 1000 | 52.6% | 47.4% | BP +18 cp | 2,454 | p < 0.01 |

| 1500 | 54.7% | 45.3% | BP +32 cp | 3,684 | p < 0.00001 |

| 2000 | 52.6% | 47.4% | BP +18 cp | 4,455 | p < 0.00001 |

| Master (2400+) | 54.1% | 45.9% | BP +28 cp | 80,918 | p < 0.00001 |

The bishop pair advantage is confirmed across all skill levels except the lowest (500 rating), where the advantage exists but is not statistically significant based on our sample size. The advantage ranges from 18 to 32 centipawns, peaking at the 1500 level. The advantage, while smaller than Kaufman's estimation of 50 centipawns, is remarkably consistent across skill levels and represents a substantial advantage in practical play. Two bishops working together control both color complexes, eliminating the single bishop's primary weakness. The consistency of this advantage across different ratings demonstrates that the bishop pair's value is fundamental to chess, not merely a product of playing strength or style.

Practical Implications

These findings have several practical applications for players at different levels:

Opening Choices: Players should be less concerned about preserving bishops in the opening unless they can maintain the bishop pair. The traditional advice to avoid trading bishop for knight may be overstated.

Middle Game Strategy: Creating positions that favor your minor pieces remains crucial, but players should recognize that knights may have a slight practical advantage even in seemingly equal positions.

Endgame Technique: Classical endgame theory remains valid—bishops excel in endgames with pawns on both sides of the board where their long-range mobility becomes crucial. Knights are superior when pawns are on one side or centralized, where their ability to attack both color complexes compensates for their limited range.

Conclusion

Our analysis of 700,000 games reveals that the assumed equality between bishops and knights requires reconsideration. In practical play with equal material, knights demonstrate a small but statistically significant advantage at most skill levels. This finding contradicts centuries of chess wisdom that slightly favors bishops.

The bishop pair advantage, however, is strongly confirmed, though at 18-32 centipawns it is smaller than the theoretical 50 centipawns suggested by previous research. This represents a meaningful advantage that justifies strategic efforts to obtain or maintain the bishop pair.

These results highlight the difference between theoretical piece values and practical performance. While bishops may possess greater theoretical potential due to their long-range capabilities, knights' tactical complexity and color flexibility give them a slight edge in practical play. Chess, ultimately, is played by humans under time pressure, where practical considerations often outweigh theoretical perfection.

The debate between bishops and knights will undoubtedly continue, but our data provides empirical evidence that in the hands of human players, from beginners to masters, the crafty knight more than holds its own against the long-ranging bishop. The fact that two pieces with such different capabilities can achieve such remarkable balance adds to chess's enduring appeal.

Methodology: Analysis based on 700,000+ games with exact material equality (identical pawns, rooks, and queens for both sides). Positions evaluated at moves 15, 20, 25, and 30 to determine qualifying games. Statistical significance determined using binomial tests (p < 0.05). Centipawn values calculated using standard win probability formulas. Amateur games sourced from Lichess (April 2025) with ratings mapped to approximate Chess.com equivalents, master games from international tournament databases.